Sustainability in Consumer Marketing

Introduction

In this chapter we will discuss some of the concepts related to sustainability in marketing. While the topic of sustainability is broad and crosses the whole business value chain, this chapter will focus on some of the key issues around sustainable consumption while providing broad context to sustainability in general. The chapter will define the core concepts of sustainability marketing as well as define the triple bottom line of planet, people and profit that need to co-exist in order to pursue the sustainability agenda. The chapter focuses on topics that consumer marketers need to be aware of in their strategic thinking. These concepts include understanding advantages and challenges in sustainability marketing as well as the dangers of falsely promoting a sustainable image. The next section will provide core definitions as well as a model to help understand the role of marketing in sustainability.

Sustainability and sustainable consumption

Sustainability is broadly defined as 'meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs [1]. For many years, consumers have accepted the behaviour of companies without questioning the negative impact that a company's actions may have on the environment and society. The primary objective of the company was to serve the needs of shareholders; everything else was secondary. In recent years, amplified by social media, consumers have started to speak up and voice their opinions about companies' unsustainable practices. This has forced many companies to look inward and review their strategies and practices.

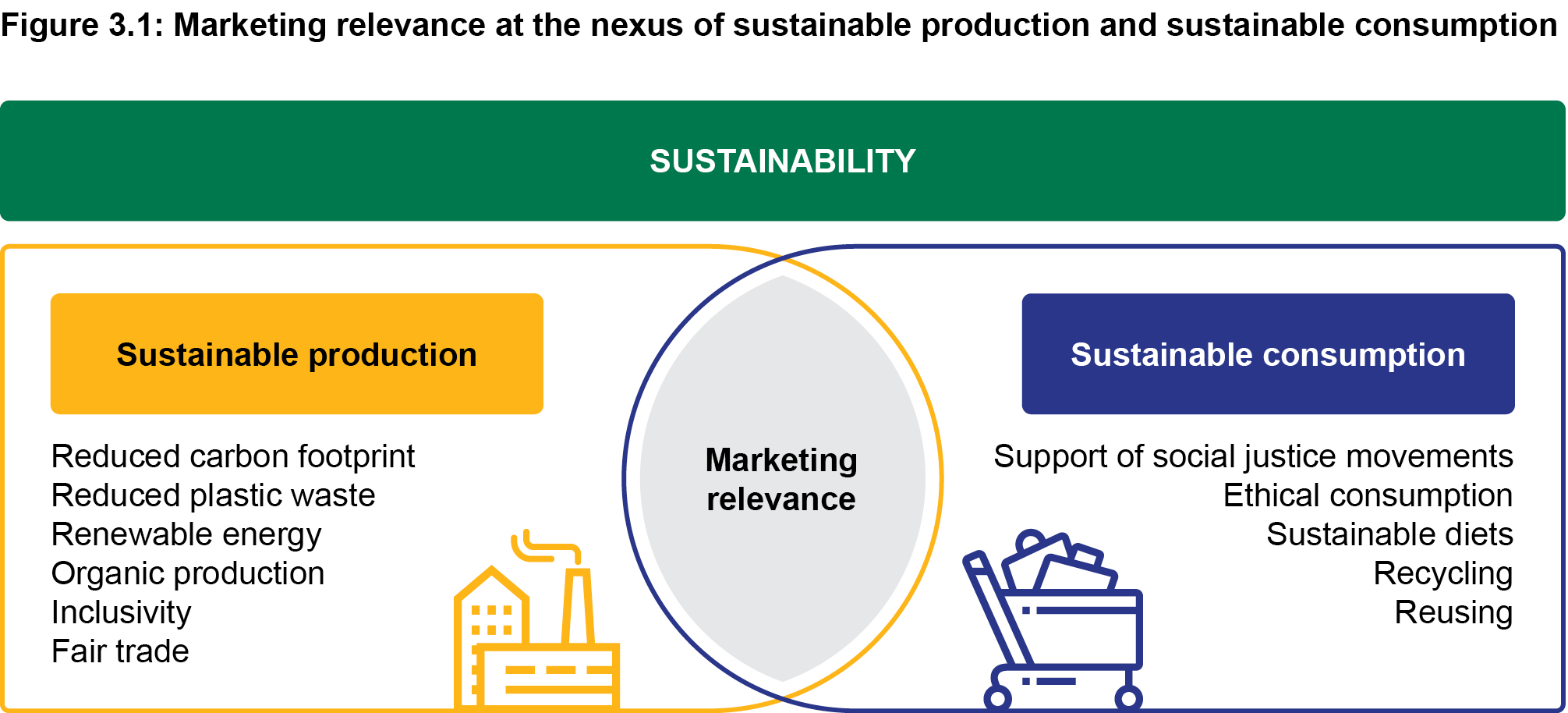

The concept of sustainability is very broad and encompasses a variety of production and consumption related themes, with consumer marketing placed at a crucial nexus in driving the agenda of sustainability as depicted in Figure 3.1.

Sustainable consumption is 'the consumption of goods and services that have minimal impact upon the environment, are socially equitable and economically viable whilst meeting the basic needs of humans, worldwide.'[2] While both the company's approach and consumer attitudes towards sustainability are important, both are evolving in their own way. For example, in some industries much of the sustainability agenda has been driven by stakeholders other than the consumer. Government legislation and sugar tax, for instance, have forced many soft drink companies in South Africa to produce more sugar-free product options. On the other hand, a growing wave of sustainable consumerism has advocated a reduction in meat products in diets and forced more plant-based alternatives in many South African restaurants and consumer packaged goods.

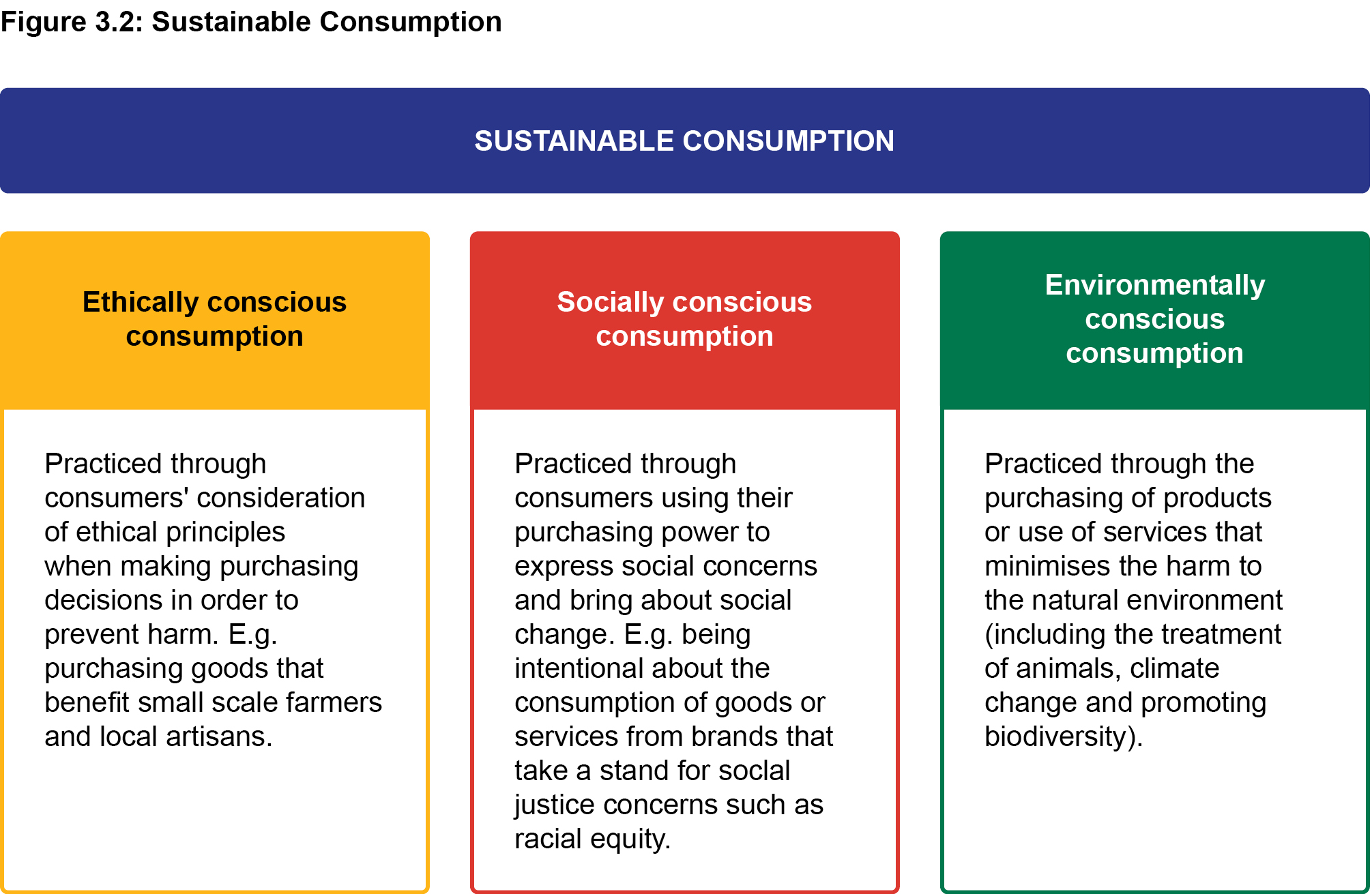

Three key pillars broadly make up sustainable consumption: 1) ethically conscious consumption, 2) socially conscious consumption and 3) environmentally conscious consumption. Ethically conscious consumption is practiced through consumers' consideration of ethical principles (aimed at preventing harm) when making purchasing decisions. An example of this may include the purchasing of goods that benefit small scale farmers and local artisans [3]. Socially conscious consumption, also referred to as socially responsible consumption, is practiced through consumers using their purchasing power to express social concerns and bring about social change [4]. This may include consumers being intentional about the consumption of goods or services from brands that take a stand for social justice concerns like racial equity. Lastly, environmentally conscious consumption, sometimes referred to as green consumerism, is practiced through the purchasing of products or use of services that minimise harm to the natural environment. Environmentally conscious consumer behaviour includes actions such a recycling, taking public transport to minimise carbon emission and paying more for environmentally friendly products [5].

With all three pillars of sustainable consumption on the rise, businesses are experiencing increased pressure from their consumers, competitors and legislators to incorporate sustainable business practices into their strategies. The expectation is for businesses to focus on more than just the short-term profit goals, but also on longer-term sustainable growth initiatives which include factors such as reducing their carbon footprint, ensuring improved livelihoods for their consumers and fostering a diverse, inclusive and equitable workplace.

The triple bottom line

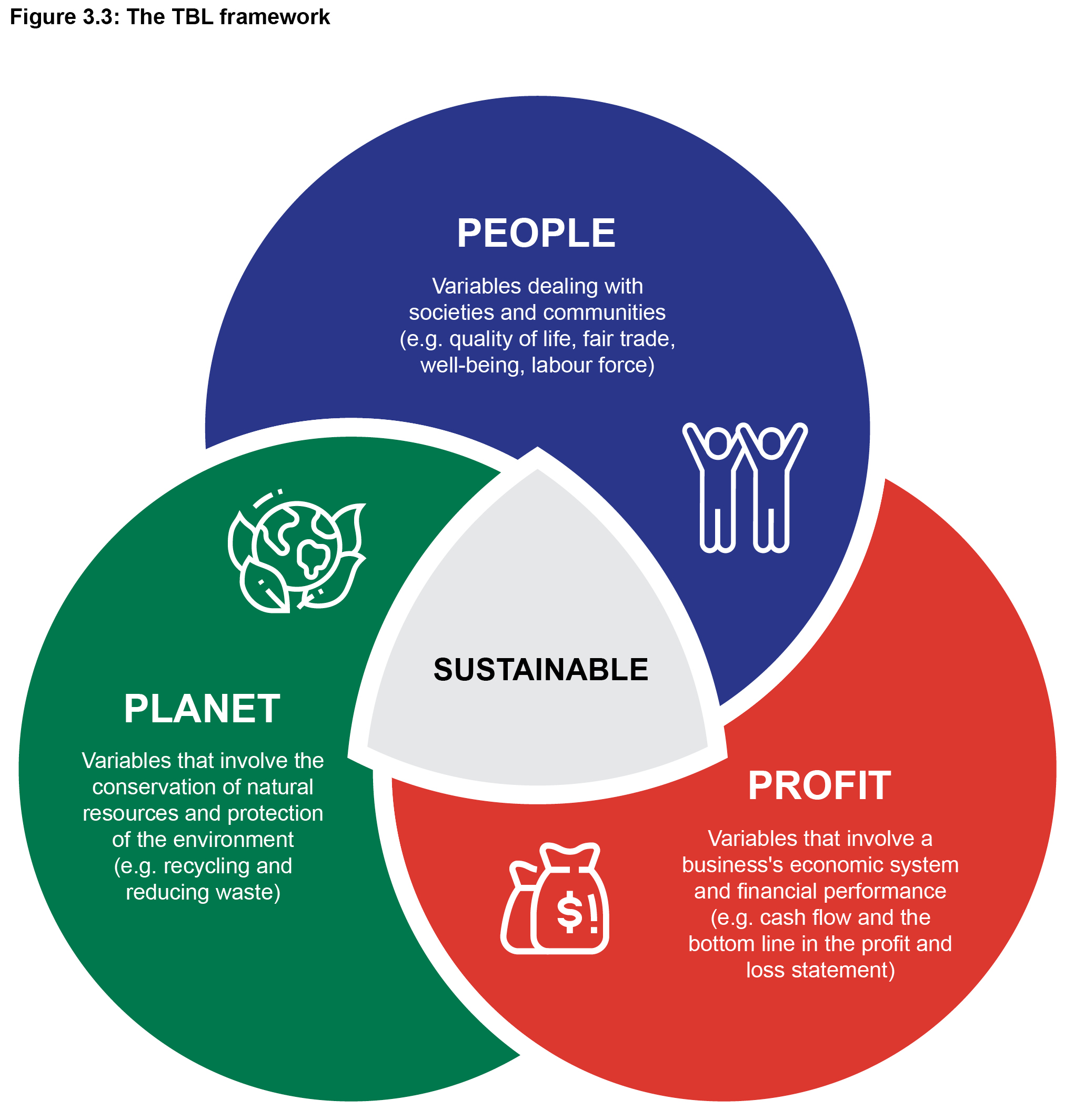

Sustainability has been a goal for many businesses over the past few decades and can be defined in many ways. One popular framework to assess the sustainability of a business is the triple bottom line (TBL). The TBL is a framework that recommends for companies to focus on social and environmental concerns just as much as they do on profits. The goal is to develop strategies that preserve the long-term viability of the people, planet and profit (the three entities that make up the triple in TBL), essentially ensuring that a business operates in a manner that is environmentally friendly, socially responsible and economically viable. The term TBL was coined by John Elkington in 1994 [6] and has since grown in popularity across the business world.

As seen in Figure 3.3, these three aspects of the TBL are interrelated and depend on each other to achieve sustainability

A 2009 analysis conducted by A.T Kearney [7] on over 90 sustainability-focused organisations in various industries revealed that businesses with practices that are aimed to operate in a way that protects the environment and improve the well-being of society whilst adding value to shareholders outperformed their industry peers. Many other studies have been conducted to illustrate the financial benefit of sustainable business practices. The following sections will dive deeper into each of the three pillars of the TBL.

Social sustainability (People)

Social sustainability is about understanding the impact that businesses have on people and the society. In his book, Cannibals with Forks [8], Elkington defined the social line of the TBL as a business operating in a manner that benefits human capital, the labour force and the community. The idea is that the business balances profit-making activities with activities that add value to society and communities.

Social sustainability takes on different meanings within different markets, industries and companies. For example, the Woolworths MySchool Programme focuses on raising funds for schools through a card system that allows Woolworths shoppers to donate funds to a school of their choice every time they shop at partner stores. Small local wine businesses, such as Palesa Wines, have a strong focus on Fair Trade. Fair Trade is the trading between companies in developed markets and producers in developing markets. The aim is to promote equality and sustainability in the farming and agricultural sectors of developing markets by paying small farmers fair prices to ensure that farm workers earn a stable income that can improve their livelihoods. All products that are supported by the Fairtrade International organisation have a Fair Trade sticker on them to communicate certification to consumers. Other ways in which businesses can get involved in social sustainability include philanthropy, volunteering and advocating for human rights.

Social sustainability is generally more effective when a business participates voluntarily, rather than doing so because it is required through regulation. Businesses that get involved in activities that benefit society tend to perform better financially and encounter other benefits, such as improved reputation, increased employee morale and improved relationships with shareholders.

Environmental sustainability (Planet)

Environmental sustainability is the second pillar of the TBL framework. Elkington defines environmental sustainability as the commitment to practices that do not compromise natural resources for future generations [9]. Natural resources are becoming increasingly scarce as consumers continue to consume goods at an exponential rate, a phenomenon known as overconsumption. A continued pattern of overconsumption leads to environmental degradation and the eventual loss of a resource base. It is important, now more than ever, to encourage businesses to adopt practices that preserve the environment and natural resources.

Popular business practices that contribute to environmental sustainability include reduction of carbon emissions, efficient use of energy resources, production of goods made with recyclable packaging [10]. Similar to social sustainability, environmental sustainability ideally has a positive impact on brand reputation and preserves the long-term viability of the business.

As environmental sustainability continues to become a topic of discussion, more and more companies will be encouraged and incentivised to participate in environmental sustainability practices and comply with the necessary standards. In South Africa, the Department of Environment, Forestry & Fisheries has set up a Green Fund to support organisations with the transition to a low carbon, resource efficient and climate resilient development path delivering high impact economic, environmental and social benefits. [11]

Economic sustainability (Profit)

The economic line of the TBL framework refers to the business's financial performance and the impact that its practices have on the economic system [12]. A business that is economically sustainable is one that is financially profitable and connects its performance to the long-term growth of the economy and contributes to supporting it. In other words, it focuses on the economic value provided by the business to its shareholders and the surrounding system in a way that makes it prosper and promotes its capability to support future generations.

When discussing economic sustainability, it is also important to discuss shared value. Shared value is a business concept that was first introduced in 2011 by Michael E. Porter and Mark R. Kramer and is defined as 'creating economic value in a way that also creates value for society by addressing its needs and challenges [13].'' In their report, Porter and Kramer discuss how businesses need to link their successes to the progress of the society in which they operate. It should not be at the peripheral of business strategies, but at the centre; the primary purpose of businesses should be redefined as creating shared value, not just profit.

Sustainable Development Goals

A more recent framework in the world of sustainability is the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs are a collection of 17 goals designed to address the global challenges we face, including, but not limited to, hunger, gender equality, poverty, climate change, justice and peace. The SDGs were set in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly and are intended to be achieved by 2030.[14]

With increased focus on sustainable business practices and the introduction of the SDGs, many organisations, globally and locally, have aligned their business ambitions to the SDGs. A year after the public announcement of the SDGs, Woolworths amended what they call their Good Business Journey Strategy to reflect the SDGs [15]. This strategy highlights Woolworths' commitment to ethical sourcing, sustainable farming, social development, transformation etc. It illustrates how their strategy aligns to the global SDGs and showcases the importance for partnership on their journey. Each year after that, Woolworths have reviewed this strategy and made necessary amends, still in line with the SDGs.

Sustainability marketing

The concept of sustainability has continued to gain attention in the global marketing sphere over the past few decades. We have seen large and small businesses get involved in sustainability marketing practices as many organisations start to realise that the sustainability component of a marketing strategy is no longer an option, but a requirement to remain competitive and impactful.

Sustainability marketing has been studied through different perspectives over the years. Today, a common definition that is used to define sustainability marketing is the process of promoting a product or service to meet the needs of present consumers without compromising the ability of future generations to fulfil their own needs. The intention is to build sustainable relationships with consumers, society and the natural environment whilst delivering financial business targets. Sustainability marketing is strongly focused on the long term. [16]

The evolving relationship between marketing and sustainability

Marketing has continuously evolved over the years, from the simple trade era of pre-industrial artisans through to the modern digital, social media and relationship-based marketing as we know it today. Towards the end of the 20th century, 'mainstream' marketing was being criticised on numerous fronts for its failure to address its socio-environmental impact. Many people believe that marketing's primary objective to drive sales is a key driver for overconsumption; and challenge the system with the notion that marketing is causing more harm than it is doing good. It is these challenges that led marketers to reconsider the traditional ways of marketing and start integrating elements of sustainability in their strategies.

Belz and Peattie list some of the previous marketing concepts that have been developed over the years: social & societal marketing, ecological marketing and green marketing [17]. Building on these earlier approaches, sustainability marketing represents a logical progression, and further integrates them all into one broad marketing approach.

The concept of social marketing was first introduced in 1971 by Kotler and Zaltman [18]. The initiatives within social marketing are intended to influence the behaviour of communities to improve their well-being. Fisk then introduced the concept of ecological marketing in 1974 as an acknowledgement of an impending ecological crisis and the willingness and ability of marketers to assume responsibility for avoiding this crisis [19]. During this period, some organisations proactively embraced environmental values as central to their business strategies. Green marketing differs from ecological marketing in that it is based more on legislative factors and regulations. According to Dam and Apeldoorn, 'Green marketing focuses on market pull and legislative push towards improved, environmentally friendly corporate performance.'[20] Sustainability marketing was the next logical step forward. As mentioned in the previous section, sustainability marketing focuses on achieving the TBL which delivers environmentally and socially sustainable solutions whilst continuing to create economic value for key stakeholders.

Sustainability marketing in practice

Although sustainability in marketing is an evolving concept, there are numerous organisations and brands that have pioneered the practice. Two of these examples are The Body Shop and Unilever as briefly illustrated below.

- The Body Shop

Dame Anita Roddick believed in businesses being a revolutionary force for good and founded British beauty and personal care company, The Body Shop, in 1976. [21] One of Roddick's famous quotes is: 'The business of business should not be about money. It should be about responsibility. It should be about public good, not private greed.' [22]

Today, The Body Shop has over 3 000 stores in 66 countries, including South Africa. The Body Shop aims to be the world's most ethical and sustainable global business. It intends to achieve this goal through initiatives such as its 'Enrich Not Exploit' commitment. This initiative is a commitment from The Body Shop to enrich its products, people and the planet. This means Fair Trade with its farmers and suppliers, helping communities thrive through its Community Trade Programme, producing products that are environmentally friendly, and being firmly against animal testing.

In 1989, The Body Shop started its first campaign to end animal testing in cosmetics – the first global cosmetics company to do so – and has continued this journey since. In 2013, The Body Shop started its relationship with Cruelty Free International, an animal protection and advocacy group. Together, the two organisations have gathered over eight million signatures for a petition to the United Nations to ban animal testing in cosmetics globally.

- Unilever/Lifebuoy

Unilever has been a global leader in the production of consumer goods since 1929. The company began when the Dutch company Margarine Unie and British soap maker Lever Brothers merged their operations and has since developed into a global giant.[23] Throughout its growth, the company has maintained excellence and as stated on the corporate website, has a simple but clear purpose – to make sustainable living commonplace. Since its inception, Unilever has taken a decisive stance in support of sustainability and recognised the need to give back to both the environment and the society, whilst still delivering economic value for its shareholders.

Unilever has over 400 brands in over 190 countries and on any given day over 2.5 billion people use Unilever products. Unilever has a strong presence in South Africa, with over 40 brands in the country. Lifebuoy, a germ protection soap brand that is well known in the country, is on a social mission to improve the health and hygiene of school children in South Africa. According to research, every year over half a million children under the age of five die due to infections such as diarrhoea globally [24]. However, a simple act like washing hands with soap could protect one in three children who get sick with diarrhoea. Despite its life- saving potential, many people and children still fail to adopt a healthy hand-washing routine, mainly due to lack of education around the topic.

This research is what inspired the launch of the Lifebuoy 'Help a Child Reach 5' campaign in South Africa in 2012. The programme intends to educate children and their families about the importance of handwashing with soap as this is one of the most effective and low-cost ways to prevent health infections [25]. Lifebuoy is also a part of the Unilever Brightfuture Schools Programme, in partnership with the South African Department of Basic Education (DBE) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). This is a 21-day schools programme that aims to educate children on hygiene and sanitation habits [26]. The public-private partnerships between Unilever, UNICEF and the DBE cannot be ignored as a key success factor for this initiative. Forming such partnerships assists in achieving a common target and ensures the necessary investment into the issues at hand.

Besides the positive impact that Lifebuoy made on the lives of millions of South Africans, implementing a social mission into the marketing strategy also resulted in improved financial performance for the brand. Unilever reported that on average, their purpose-led brands such as Lifebuoy grew 69% faster than the rest of the business in 2018 and 49% faster in 2017 [27]. Lifebouy was also one of the first brands to use their platform as a means to educate on the benefits of hand washing during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

False sustainability: Greenwashing and woke- washing

The word sustainability has fast become one of the most overused buzzwords in the business world. While it is important that companies are starting to speak up about the importance of sustainability, misuse and misunderstanding of the concept has caused some businesses to lose sight of what sustainability truly means and why it is important for businesses to adopt sustainable business practices in the first place. Many organisations have jumped onto the sustainability bandwagon, but not all of them have necessarily implemented sustainable models and practices that genuinely do good for the environment and society.

The environmental movement gained momentum in the mid-1960s and prompted many businesses to create a new environmentally sustainable image through their marketing efforts. As more and more companies realised the profitability benefits of 'going green', the risk of greenwashing increased. 'Greenwashing' is the use of marketing to make misleading or unsubstantiated claims about the environmental benefits of a business's products or services [28]. The general intent behind greenwashing is for a business to create a benefit by appearing to be environmentally responsible, even though it is not.

With climate change and environmental sustainability being a hot topic in business today, greenwashing is something that we see many brands partake in. In 2015, the German car manufacturer Volkswagen was implicated in one of the decade's biggest greenwashing scandals, 'Dieselgate' also known as 'Diesel Dupe'[29]. For many years, Volkswagen promoted 'clean diesel' in their marketing campaigns, an alternative to hybrid and electric vehicles. However, in September 2015, the Environmental Protection Agency in America found that Volkswagen had installed software devices in many of their vehicles.

These software devices enabled the rigging of vehicle carbon dioxide emission test results and reflected levels that were regulatory compliant, even though the vehicles emitted nitrogen oxide pollutants up to 40 times above the US federal limit. Volkswagen deployed this programming software in roughly 11 million vehicles globally.

Repercussions for Volkswagen after this scandal have been severe. The brand lost the trust of many of its consumers. Financial implications included legal fines, the cost to recall affected vehicles, and the stock price plummeted after the scandal. The scandal also had a negative halo effect on other German car brands in America[30]. Up until that point, German car manufacturers had routinely advertised the benefits of 'German engineering' in their U.S. marketing campaigns, creating a reputation group in consumers' minds. When the Volkswagen scandal broke, consumers associated German-made vehicles such as Mercedes-Benz and BMW with those made by the Volkswagen Group. It was reported that the sales of other German car brands decreased by approximately USD 26.5 billion due to this spillover effect.

A newer term that has gained popularity in the business world is 'woke-washing'. As conversations on sustainability marketing and brand activism advance into wider spaces such as politics and social justice, we start to see more brands release socially and politically aware advertising focused on gender equality, racial equity and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and Ace (LGBTQIA+) justice, to name a few. The term 'woke- washing' is derived from the slang word 'woke', which can be defined as 'being conscious of racial discrimination in society and other forms of oppression and injustice'31. Woke-washing resembles the concept of greenwashing in that it is the dissonance between marketing and a company's behaviour. Instead of environmental issues, woke-washing focuses on businesses' use of marketing to make misleading or unsubstantiated claims about social justice-related matters. As a myriad of social issues consume the global dialogue currently and predictably in time to come, brands are trying to figure out how they fit into the discussion. Some brands get it right, but many do not.

June is globally recognised as Pride Month, a month where the impact and fight of the LGBTQIA+ community is recognised and celebrated across the globe. As the support for LGBTQIA+ rights has increased over the years, so has the incentive for brands to position themselves in alliance with the cause. Over the past few years, we have seen a rise in rainbow flags (a symbol of the LGBTQIA+ community) across various marketing campaigns in the form of branded merchandise, public storefronts, company brand logos across social media, and so much more. However, this is continually raising the question: Are these organisations truly supporting and contributing to the LGBTQIA+ community, or is it all just branding? Whilst some of the profits generated during these campaigns do go to LGBTQIA+ non-profits, many brands don't necessarily support the LGBTQIA+ community but still benefit from consumers who purchase their goods under the notion that that their purchase contributes to the LGBTQIA+ community. Apparel brand, H&M launched its first Pride collection in The US in 2018 and donated a percentage of the proceeds to a non-profit organisation focused on LGBTQIA+ rights. Although a portion of these proceeds were going to a LGBTQIA+ non-profit, H&M was later criticised for working with suppliers in countries that criminalised homosexuality and transgender individuals[30].

While it can be argued that these marketing campaigns are successful in bringing awareness to the cause, many activists in the LGBTQIA+ movement and other social justice movements have challenged brands to graduate their actions and intentions from awareness to institutional reform and abolishment. They feel that the involvement of brands in movements like Pride Month have become less about inclusivity and fighting for the cause and more about a marketing opportunity.

The rise in greenwashing and woke-washing by brands has increased consumers' scepticism of brands, especially amongst younger consumers[31]. Consumers are much more aware that they are being marketed to and are quick to recognise and call out when a brand is being inauthentic in its marketing campaigns. Criticism of the impact of sustainability marketing and brand activism has also grown amongst marketers themselves. While some case studies indicate that brands can achieve success by having a greater purpose than just achieving sales (eg., Dove, Lifebuoy, Patagonia and the like), marketers are also realising that not every brand needs to embrace a 'sustainable purpose'. It is more important that brands are straightforward and clear about their vision and mission than to force-fit a purpose that the brand does not live up to and is not part of the wider company values and culture.

The advantages and challenges of sustainability marketing

When engaging in any sustainable business practices, it is important that businesses focus not only on the brand advantages, but also on the actual impact that the business will have on the environment and society at large. A business that practices sustainability marketing could have a competitive advantage over one that does not.

Advantages

Besides the external positive impact on the economy, society and environment, incorporating sustainable practices into the business strategy can also benefit the company itself. Below are some examples of the advantages of implementing sustainability into the business strategy.

- Improved brand image

A good brand image is arguably one of the most valuable assets a business holds and maintaining it is a key priority for many businesses. Over the years, consumers have become increasingly invested in knowing more about the products that they use. They want to know whether brands are contributing to the improvement of the environment and the societies in which they operate. Younger generations have been known to express interest in making a positive impact in the world and they find that using brands with sustainable practices allows them to do this in some small way. Implementing sustainable business practices helps boost an organisation's reputation amongst these consumers and builds a stronger long-term relationship with them, as they are more inclined to identify with and support brands that are operating with an objective beyond generating profits.

- Possible cost saving

Cost saving is one of the biggest motivators for organisations. Integrating sustainable practices into the business model can lead to efficient operations and reduced costs, even though it might require a large capital investment. Cost saving can be derived from limiting the use of natural resources (such as water and electricity), reducing and recycling waste, and signing up for energy-saver incentives. The cost savings from these initiatives tend to actualise in the long run, not immediately.

- Attract new employees and retain existing customers and investors

Employees want to be associated with businesses that are 'doing good' and are intentional about their involvement in social and environmental initiatives. Some research shows that younger generations, which make up more than 30% of the working population globally, have high expectations for the actions of businesses when it comes to social and environmental matters and they want to work for companies that uphold these values[32].

- Responsible innovation

Innovation is key to remaining competitive in the marketplace. Customers are interested in businesses that are creating products and services that positively impact the environment and society at large. By being intentional about their involvement in sustainable practices, businesses are forced to innovate in a responsible and creative manner.

Challenges

Although sustainability marketing creates a competitive advantage, organisations also face challenges when it comes to the topic. Below are a few challenges businesses face when implementing a business plan that encompasses an element of sustainability.

- The switch can be expensive

It takes time for businesses to change their strategies and the development of a new strategy usually translates into increased initial costs. Although sustainable practices are recognised as long-term cost-saving initiatives, the upfront implementation costs are usually high. For example, choosing to transition to solar energy to replace electricity generated from a coal- fired power station would require the installation of solar panels which can be costly.

- Increased product prices

In some cases, the switch to more environmentally friendly products can lead to higher production costs such as paying more for fair labour and using sustainable material that costs more to grow and manufacture. The increase in costs can either be absorbed by the business in terms of accepting lower profit margins on the products produced, or they can be passed along to the consumer in the form of higher product prices. The increased production costs and subsequent price increases could result in decreased demand and product sales as consumers switch to more affordable alternatives.

- Difficulty fulfilling all three TBL pillars

Although sustainability is on the rise, profit generation remains a key objective for several businesses. Many people believe that by including a social and environmental improvement goal to the strategy takes the focus off the purported main economic goal – to generate profit.

Not all companies can adequately satisfy all three pillars of the TBL. In most cases, when put in this position, companies tend to prioritise economic profitability over environmental and social sustainability practices.

- Consumer scepticism due to greenwashing and woke-washing

As increasing numbers of companies realise the benefits of implementing sustainable practices into their business strategies, the risk of greenwashing and woke-washing increases. Due to the false-sustainability claims made by brands, many consumers have grown sceptical of brands that claim to be environmentally or socially sustainable. Consumers, especially younger generations, are scrutinising all sustainability marketing campaigns and are quick to spot when a campaign is authentic or merely a brand awareness initiative.

- Educating consumers about sustainable products

Education is crucial in facilitating the shift towards sustainable consumption. However, this can be a challenge, especially in markets where conversations around sustainability are still in their infancy stages. Even though consumers might want to adopt sustainable consumption behaviour, they are often unsure of how and where to begin. This is where companies play a big role in facilitating this move towards sustainability and ensuring that consumers are educated on the topic. Ways that companies educate consumers include information on product packaging, on digital platforms and in advertising messages. The increased focus on sustainability and shift towards sustainable practices highlights the importance of such topics being taught in schools and earlier in people's lives.

Sustainable consumption in South Africa

As discussed throughout the chapter, sustainable consumption, whether it be ethical, social or environmental, simply means engaging in the economy and consuming goods and services with more awareness around how your consumption impacts the environment and society at large. When discussing sustainable consumption in South Africa, several factors need to be considered.

With a Gini Coefficient of 0.63, South Africa is a country with one of the highest levels of economic inequality in the world[33]. Inequality manifests itself through skewed income distribution and unequal access to opportunities. The high unemployment rate of 27% (as of 2019) continues to heavily contribute to the persistence of inequality in the country[34]. The median wage in South Africa is reported to be R3,300, and supports on average 3.5 people, meaning that the average South African household can barely afford expenses which low income households may typically be expected to cover e.g. food, transport, burial insurance etc.[35]

Affordability and education levels around sustainability are factors which cannot be ignored when discussing sustainable consumption in the South African context. Sustainable products tend to be more expensive, and consequently aren't necessarily a feasible option for most South African consumers.

It is important to note though, that even though poorer households can't always afford sustainably produced products or aren't always aware of the technicalities around sustainability, it is these communities that tend to lead the most sustainable lives in the country (e.g. low carbon footprint and low water usage). Unfortunately, though, these are the communities that are disproportionately impacted by the negative side effects of unsustainable business practices. In most countries, low income communities depend heavily on natural resources for their livelihoods and survival and are most vulnerable to environmental changes. As a result, continued degradation of the environment due to unsustainable business practice impacts theses communities most.

Any misconceptions around South Africans not caring about sustainability fail to acknowledge the economic reality of the country. With pressing issues such as poverty, unemployment and inequality on the rise, it becomes very difficult for the average South African consumer to fully engage in sustainability topics that do not tackle some of these urgent matters. Several sustainability initiatives are designed for the wealthier, more privileged consumers in the country.

A big responsibility lies with large organisations to encourage sustainable consumption across all consumer segments in the country. Furthermore, South African organisations need to aim for better sustainable business practices; too many firms still rely heavily on fossil fuels and do not positively contribute to the society in which they operate. Additionally, organisations need to explore innovative ways to make sustainably produced goods and services more affordable and accessible for the average South African consumer.

Conclusion

Often business growth is framed around consuming (and hence producing) more. This dynamic involves the consumption of resources. Sustainability principles are however rooted in conserving the resources and consuming less. It is critical that companies find the balance between the two imperatives so that profits can be made whilst protecting the environment. Businesses also need to recognise the role that they play in the society in which they operate. If brands are going to have marketing campaigns that speak out against social injustices, the brands need to play a role larger than just building awareness on the issues – they need to start acting on important matters that will have the needed positive impact.

Implementing a marketing strategy that focuses on sustainability has several advantages for the brand and business, but not all brands need to be 'purpose-led'. The desire to have a purpose when it is not authentic is a key driver in greenwashing and woke-washing, which has evidently tainted the reputations of legacy brands and lost the favour of their consumers.

As discussed earlier, an increasing number of consumers have begun to question a brand's motivation for engaging in environmental and social issues and will look for the actions that support the marketing communication and claims. If brands are to target these consumers and speak out about environmental and social sustainability, they need to ensure authenticity, transparency with their consumers, and consistency with their wider company values and culture. Furthermore, they need to keep in mind the economic nuances that hinder sustainable consumerism in the South African context and not apply a blanket approach. It is more important that brands communicate a straightforward, clear and accurate vision and mission than to force-fit and falsely communicate a sustainability message that is not true and genuine.